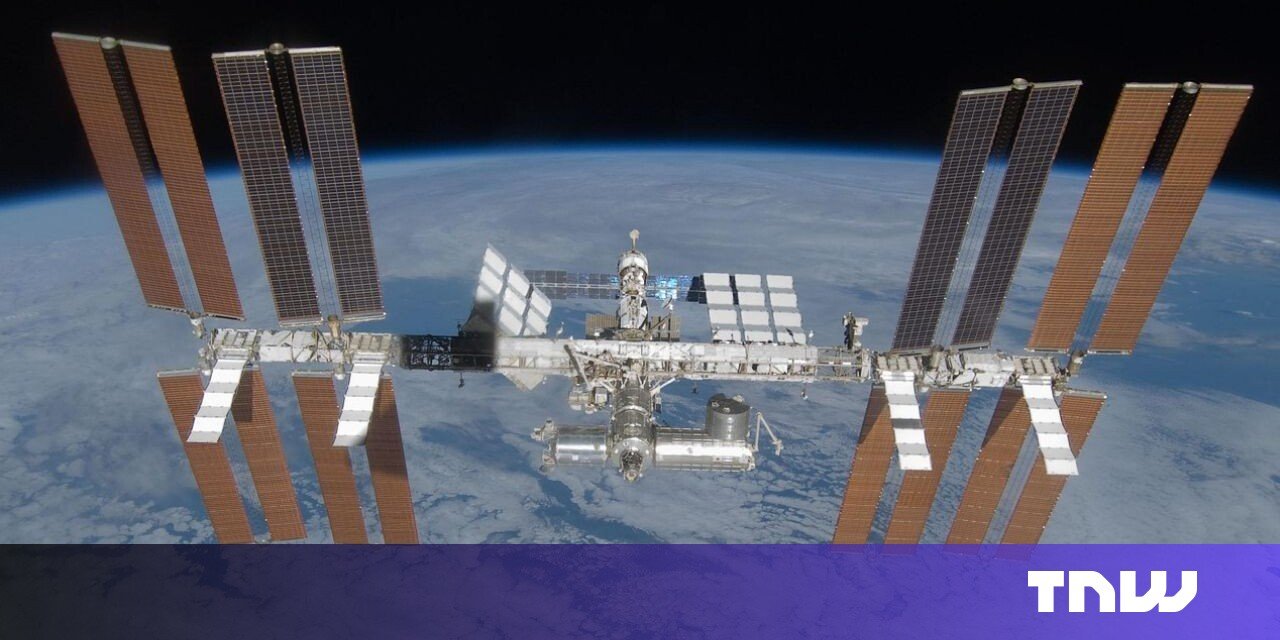

The world’s first metal 3D printer for space is on its way to the International Space Station (ISS), where it will be installed in ESA’s Columbus module. Its mission is to demonstrate the technology’s validity in orbit and pave the way for future use on Mars and the Moon.

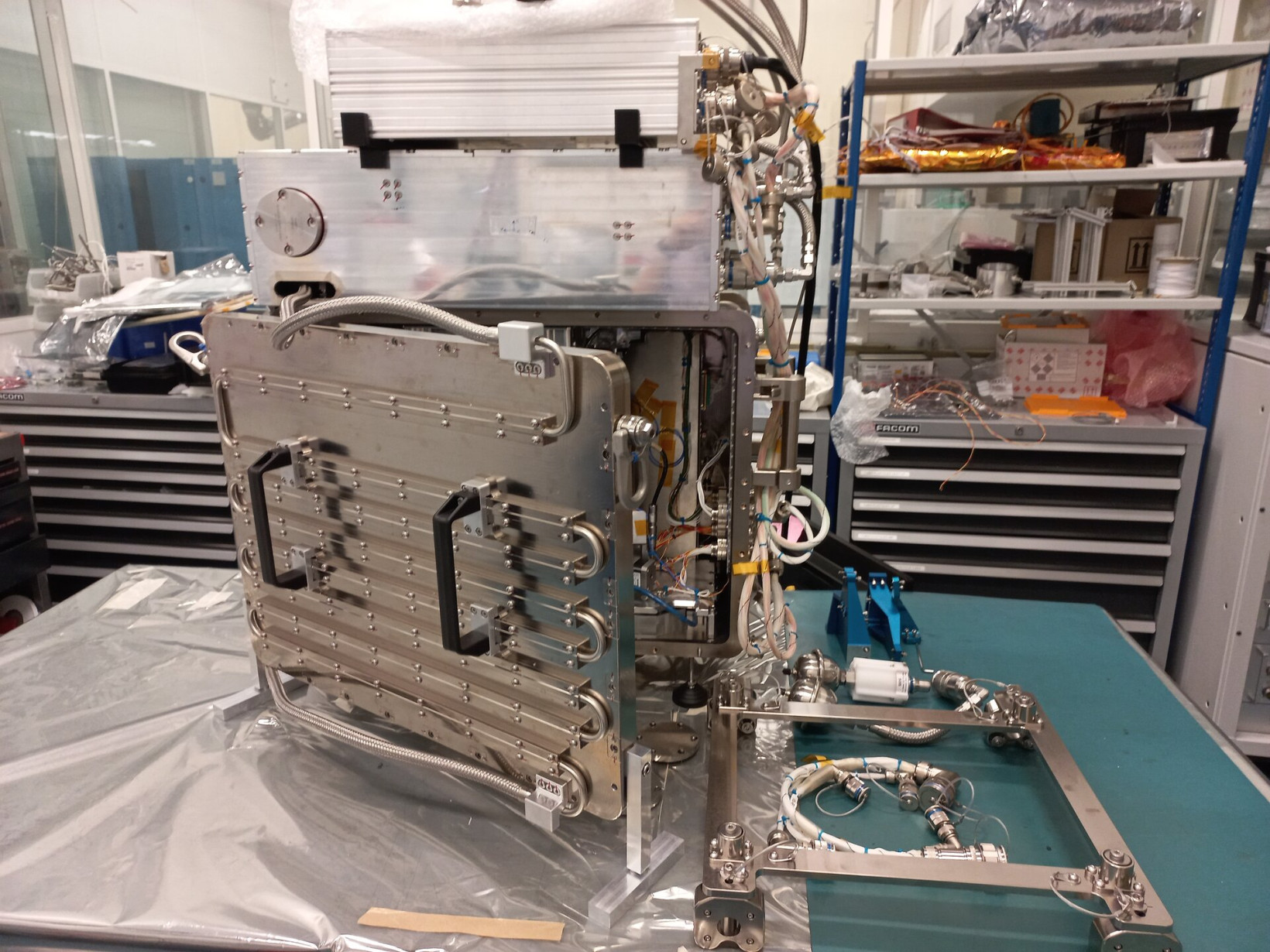

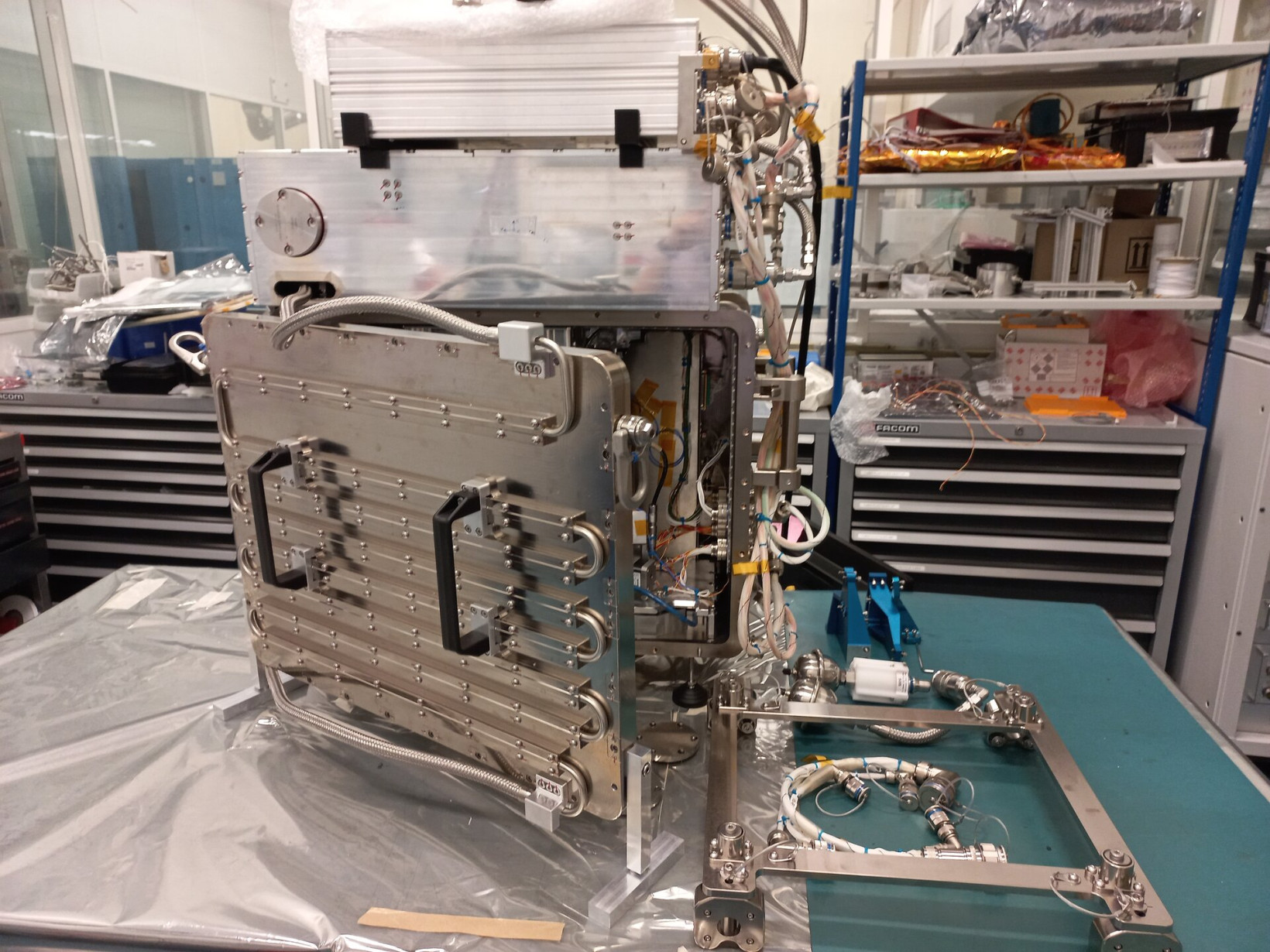

The 180 kg printer developed by Airbus is used to repair or produce tools, assembly interfaces and mechanical parts. Parts with a volume of nine centimeters high and five centimeters wide can be printed, with the process taking about 40 hours.

Once installed on the ISS, the 3D printer will produce four metal samples that will be sent back to Earth for analysis. The ground-based technical model of the printer will also produce the same copies.

The four test prints. Photo credit: Airbus Space and Defense SAS

“To assess the effects of microgravity, ESA and the Danish Technical University will carry out mechanical strength and bending tests as well as microstructural analyzes on the parts manufactured in space and compare them with the other samples,” says Sébastien Girault, systems engineer for metal 3D Printer at Airbus, explained.

Manufacturing in space: the new frontier

Manufacturing in space has emerged as a new frontier for both research and improved space exploration capabilities.

The <3 of EU technology

The latest rumors from the EU tech scene, a story from our wise founder Boris and questionable AI art. It’s free in your inbox every week. Join Now!

When it comes to research and development, the properties of space – its microgravity, near-vacuum state and higher radiation intensity – provide a unique testing ground for sectors from semiconductors to pharmaceuticals.

At the same time, the ability to repair or produce parts in space reduces dependence on supplies from Earth and is therefore critical for expanded exploration and life support in space.

“Increasing the maturity and automation of additive manufacturing in space could be a game-changer in supporting life beyond Earth,” said Gwenaëlle Aridon, senior engineer at Airbus Space Assembly.

“If you think beyond the ISS, the applications could be amazing. Imagine a metal printer using transformed regolith [moondust] or recycled materials to build a moon base!”

The Metal Age of Space

3D printing of plastic parts on board the ISS has been carried out since 2014. However, metal printing in space presents a number of challenges.

The first is size. To do this, the printer had to be reduced to the dimensions of a washing machine; In comparison, floor printers take up at least 10 square meters, according to Girault.

The 3D metal printer. Photo credit: ESA

The 3D metal printer. Photo credit: ESA

Another challenge is security. A metal 3D printer not only works at higher temperatures, but also requires a powerful laser to melt the metal.

“The melting point of stainless steel is around 1400°C, so the printer operates in a completely sealed enclosure, preventing excess heat or fumes from reaching the space station crew,” said Advenit Makaya, materials engineer at ESA.

“And before printing begins, the printer’s internal oxygen atmosphere must be vented into space and replaced with nitrogen – the hot stainless steel would oxidize if exposed to the oxygen.”

If the 3D printer delivers the desired results, the technology could prove crucial for Mars and Moon exploration, while contributing to ESA’s vision for a circular space economy.

“If this technology demonstrator proves successful, it will open the way to printing metal parts in space, in the event that a metal part breaks and needs to be replaced, or if a special tool is needed that is not yet available,” says Rob Postema, ESA’s technical officer told TNW.

“In both cases, a resupply mission is not necessary. The next steps in the development and maturity of metal printing in space could include printing larger parts and using different metals.”

Update (8:10 a.m. CET, February 2, 2024): The article has been updated to include Rob Postema’s commentary.