The Herald, E-Tangata and Tawera Productions have teamed up to bring you Waka, a six-part online video series that traces the cultural revival of traditional canoeing skills by four teams from across the Pacific. Today Simone Kaho meets Derek Kawiti, who is trying to make a waka out of a 3D printer.

Click the video above to watch episode 5

On the banks of the Hōteo River, which flows next to the Hihiaua Cultural Center in Whangārei, the architect and design lecturer Derek Kawiti spits muddy mud into a bucket.

He’s doing a waka for the Rāta carving symposium, but the canoe carvers in the Hihiaua workshed would in no way recognize it. There is no log and no carving.

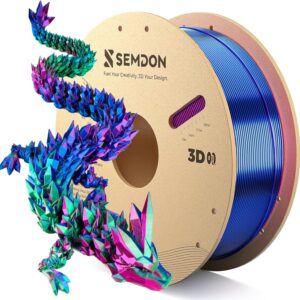

Derek’s challenge is to create a full-size replica of a 230 year old Hawaiian outrigger canoe – wa’a in Hawaiian – using the latest in 3D printing technology.

The real thing is sitting in the Smithsonian in Washington DC, USA, which was donated by Queen Kapi’olani of Hawaii in 1887 when it was 100 years old. It is the oldest Hawaiian wa’a in the world.

Derek never touched it. He works with a 3D scan sent by the Smithsonian.

While the waka carvers work on their logs – chainsaws, chipping with adzes, and bows – Derek collects their shavings and wood shavings from the large blue container they are tipped into.

Later he drives the chips and muds to Wellington. In his workrooms at Victoria University, he uses these ingredients to mix a polymer paste that almost explodes the injector of the large robot he uses to 3D print the Wa’a.

So this is a failure. He returns to the drawing board – in this case, his computer.

Related articles

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/O35SWM5IQJQKJQJFNKVNBKRTKE.jpg)

It is a groundbreaking project aimed at exploring what 3D printing could mean for the future of waka carving and how waka artifacts can be restored and made available to the public and the Pacific communities from which they originate.

While 3D printing and scanning have been used by museums for some time, offering new ways to obtain, examine on-site, and display artifacts, this is the first project to include a life-size replica of an ancient Pacific Wa’a.

It raises some interesting questions.

“Obviously,” says Derek, “it could replace the craftsman’s role in building waka or wa’a. So what kind of major traditional usual roles is it taking away and what is it replacing?”

The idea for the project goes back to 2016 when the Smithsonian hosted the Māori exhibition Tuku Iho.

James Eruera, the creative force behind Rātā, took part in the exhibition with his waka students from New Zealand’s national canoe school Te Tapuwae o te Waka. They had carved a tōtara waka as a present for the museum.

Something had changed for Smithsonian curator Joshua Bell, and he brought her to Queen Kapi’olanis Wa’a. James was so excited he ran outside to call Ray and Alika Bumatay, the father and son’s master Hawaiian carver. He told them, “Here is this beautiful Wa’a, and I think it’s really worth a look.”

With the help of the Smithsonian, James and the Hawaiians were soon back at the museum to study and repair the Wa’a.

The Smithsonian had already done a 3D scan of the Wa’a and preliminary plans were being made for the print.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/H4CGGNKSYUIRJ5HCEPXZSVXBWE.jpg)

Then, back in Aotearoa, James met Derek Kawiti by chance, he says.

“Or maybe the Wa’a just wanted us to meet,” says James. “Maybe the whole project just wanted to happen with all of us in tow.”

Derek taught computer design at the School of Architecture at Victoria University. He had completed his Masters at the Design Research Lab in London and then spent 14 years in London, the Caribbean and Italy before returning to Aotearoa to teach. He was already using 3D printing and other digital tools like artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR).

And it just so happens that his research was mainly about “understanding the impact of digital technologies on convergence with traditional indigenous knowledge”.

When he grew up in Patea, he was unexpectedly surrounded by waka. “We used to only find them sticking out of the mud in the paddock. They used to come through peat swamps.”

Seeing that Derek had unique credentials to get the project off the ground, James suggested it be part of the Rātā Symposium, and the Smithsonian kicked off the plan.

However, it took a while to create a memorandum of understanding that set out the strict terms and conditions for using the scan. And it wasn’t until Rātā started that Derek finally got the 3D scan. That didn’t leave much room for experimentation with materials.

The silt and shavings, for example, were a failed attempt to link culturally contextual materials to the printed Wa’a.

“I’m afraid that what I’m doing really stinks and isn’t good enough,” says Derek. “We don’t really want to worsen or reduce the perception of the original.”

He doesn’t have to worry. The finished replica of Queen Kapi’olani wa’a is long, curved and elegant. It consists of a light wooden thread, a buttercream color with an unusual layered structure.

At the start of Rātā waka in Kororāreka, Russell, Derek acknowledges “that this (wa’a) has traveled through time to rejoin us”.

It’s not seaworthy – that wasn’t the goal this time – but the next version could be.

/cloudfront-ap-southeast-2.images.arcpublishing.com/nzme/P5LOM3OXQEHMN3QWXQT4W4PI3A.jpg)

While the other waka, bronzed and powerful, glide in the sea, the replica wa’a stays on land looking separate and vulnerable – like a grandma who has come to watch or a much younger sibling who is too young to go along . In a way, it’s both.

“I think a good thing about this exercise is that people will see that 3D printing is far from perfect,” says Derek. “I always think that it will be subordinate to the finer aspects of human engagement.”

Waka was made with support from NZ On Air.